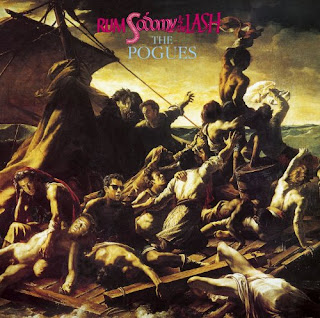

For our first review, we're going to look at The Pogues' seminal 1985 release Rum, Sodomy, and the Lash. Produced by none other than Elvis Costello, Rum Sodomy put The Pogues on the map as the pioneering band of the Irish punk-folk movement.

|

| Géricault's Raft of the Medusa featuring The Pogues |

I've known about The Pogues for a few years; listening to bands like Flogging Molly it's almost impossible not to at least hear about the band that first fused Irish traditional music with a punk mentality. Somehow, I'd never managed to actually give them a full listen until just this year when I finally crossed Rum Sodomy off my "why don't I own this yet" list. Truth to tell, I wasn't exactly certain what to expect. So I was a little surprised when to hear a more traditional-inspired album than a three chord angry punk album with some pipes and a fiddle overlaid.

Surprised, but not unpleasantly so. I found an album much more grounded in traditional Irish music--though some traditional Irish folk musicians of the time, such as the titular subject of "Planxty Noel Hill" from the Poguetry in Motion EP, felt what the band was doing was an affront to "pure" Irish folk. It's largely an acoustic album, driven by Jem Finer's banjo and James Fearnly's sometimes mournful accordion. Spider Stacey's pipes provide lively counterpoint, with the rhythm section of Cait O'Riordan (who provides haunting vocals on "I'm a Man You Don't Meet Every Day," one of the album's three traditional covers) and Andrew Rankin keeping them grounded.

Leading the pack, of course, is Shane MacGowan. Long known for his self-destructive behavior, MacGowan tears through the vocals on Rum Sodomy with a voice that could grind glass, much in the tradition of the late Ronnie Drew of the Dubliners, whom The Pogues would later collaborate with in a few television appearances and recorded singles. His delivery is a frenetic staccato that he manages to slow down into a powerful, solemn delivery in several songs whose brutal, sobering lyrics require that sobering tone. He even manages a hilarious falsetto on "The Gentleman Soldier."

MacGowan is the primary lyricist on Rum Sodomy, writing all five of the non-instrumental original songs on the album. This would change over the next few albums he did with the group, but for now it's his gutter prose that dominates. Listening, one might think that he's preoccupied with drinking. No surprise given the stories about the binges the band went on while recording the album. But the real theme that's consistent throughout the entire album is death. Yes, from the drunken star of "The Sick Bed of Culchulainn," who literally drinks himself to death (though he leaps out of his coffin at the end demanding further libation) to the lost and battered soul of "The Old Main Drag," who has given up everything to the seedy underside of London and longs for release. From where the narrator of "A Pair of Brown Eyes" first sees them amidst the death and destruction around him to the whimsical end of Billy in "Billy's Bones," death surrounds on the album.

Even the traditional arrangements and the covers deal with death and dying, dead and buried workers in "Navigator," the raucous, country-influenced "Jesse James," and the soberly delivered "And the Band Played Waltzing Matilda," Eric Bogle's scathing critique of war and its aftermath. MacGowan is at his mournful best on this song in particular, singing with enough real bitterness that you'd almost believe he was narrating from personal experience. This, along with "The Old Main Drag" are the most sobering and brutal of all the songs on the album; tales of wasted life and lost youth. The realism is a welcome change from much of the other music of the time, equally depressing but without the "I'm so sad, so so sad, so please pity me" attitude of much of the alterno-pop of the day.

But it's not all bleak. Despite the heavy subject matter much of the album is very upbeat in tempo, and the arrangement of the tracks usually gives you little time to dwell on the sorrow, the band's dragging you off on another drunken adventure. Much like the history of Ireland itself, the pain and sorrow and brutal reality are part of a greater tapestry giving a rich musical experience.

Curiously, despite the extent to which the album is rooted in traditional Irish music, there's not a whole lot of actual subject matter dealing with Ireland or the Irish experience. Even the traditional and cover songs deal very little with Irish identity, something that's touched upon to a much greater extent in The Pogues' 1988 release, If I should Fall From Grace With God, a somewhat more musically diverse album. Not that this is a drawback for Rum Sodomy, as it shows that Irish-influenced music doesn't need to rely specifically on national identity, or the notion of the "Paddy" persona.

It's hard to determine if Rum Sodomy is my favorite Pogues album--that honor might have to go to the aforementioned Grace With God. But Rum Sodomy was my first real exposure to The Pogues and an even deeper connection to what can be done with Irish music and a punk attitude. I once said to a friend, half in jest, that discovering The Pogues was like finding religion. But the more I think about it, it's probably pretty close to the truth.

Just a few final notes. This version of the album is the 2004 re-release which includes a few bonus tracks and the entirety of the Poguetry in Motion EP that was released in 1986. Among the notable tracks are "A Pistol for Paddy Garcia," which sounds like an Ennio Morricone spaghetti western track by way of Dublin, and "Body of an American," which actually does speak in part to the Irish-American experience, and has been featured in a number of episodes of HBO's The Wire.

Well, that's number one down. Not sure if I know what I'm doing yet but what the hell. Next up, I dip back into my progressive past for Traffic's fourth effort, John Barleycorn Must Die.

No comments:

Post a Comment